Virtual fixture

A virtual fixture is an overlay of abstract sensory information on a workspace in order to improve the telepresence of a remotely manipulated task.

Contents |

Concept

The concept of virtual fixtures was first introduced in (Rosenberg, 1993) as an overlay of abstract sensory information on a workspace in order to improve the telepresence in a telemanipulation task. The concept of abstract sensory overlays is difficult to visualize and talk about, as a consequence the virtual fixture metaphor was introduced. To understand what a virtual fixture is an analogy with a real physical fixture such as a ruler is often used. A simple task such as drawing a straight line on a piece of paper on free-hand is a task that most humans are unable to perform with good accuracy and high speed. However, the use of a simple device such as a ruler allows the task to be carried out fast and with good accuracy. The use of a ruler helps the user by guiding the pen along the ruler reducing the tremor and mental load of the user, thus increasing the quality of the task.

The definition of virtual fixtures in (Rosenberg, 1993) is much broader than simply providing guidance of the end-effector. For example, auditory virtual fixtures are used to increase the user awareness by providing audio clues that helps the user by providing multi modal cues for localization of the end-effector. Rosenberg argues that the success of virtual fixtures is not only because the user is guided by the fixture, but that the user experiences a greater presence and better localization in the remote workspace. However, in the context of human-machine collaborative systems, the term virtual fixtures is most often used to refer to a task dependent aid that guides the user's motion along desired directions while preventing motion in undesired directions or regions of the workspace. This is the type of virtual fixtures that is described in this article.

Virtual fixtures can be either guiding virtual fixtures or forbidden regions virtual fixtures. A forbidden regions virtual fixture could be used, for example, in a teleoperated setting where the operator has to drive a vehicle at a remote site to accomplish an objective. If there are pits at the remote site which would be harmful for the vehicle to fall into forbidden regions could be defined at the various pits locations, thus preventing the operator from issuing commands that would result in the vehicle ending up in such a pit.

Such illegal commands could easily be sent by an operator because of, for instance, delays in the teleoperation loop, poor telepresence or a number of other reasons.

An example of a guiding virtual fixture could be when the vehicle must follow a certain trajectory,

The operator is then able to control the progress along the preferred direction while motion along the non-preferred direction is constrained.

With both forbidden regions and guiding virtual fixtures the stiffness, or its inverse the compliance, of the fixture can be adjusted. If the compliance is high (low stiffness) the fixture is soft. On the other hand when the compliance is zero (maximum stiffness) the fixture is hard.

Virtual Fixture Control Law

This section describes how a control law that implements virtual fixtures can be derived. It is assumed that the robot is a purely kinematic device with end-effector position ![\mathbf{p} = \left[ x,y,z \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/29ead46fecdb89762d799223f30e937e.png) and end-effector orientation

and end-effector orientation ![\mathbf{r} = \left[ r_\textrm{x}, r_\textrm{y}, r_\textrm{z} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/346517ef40526c8d472a7161e7ffde0a.png) expressed in the robot's base frame

expressed in the robot's base frame  . The input control signal

. The input control signal  to the robot is assumed to be a desired end-effector velocity

to the robot is assumed to be a desired end-effector velocity ![\mathbf{v} = \dot{\mathbf{x}} = \left[ \dot{\mathbf{p}}, \dot{\mathbf{r}} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a955e588a2265cb7808895c2ace3f7d8.png) . In a tele-operated system it is often useful to scale the input velocity from the operator,

. In a tele-operated system it is often useful to scale the input velocity from the operator,  before feeding it to the robot controller. If the input from the user is of another form such as a force or position it must first be transformed to an input velocity, by for example scaling or differentiating.

before feeding it to the robot controller. If the input from the user is of another form such as a force or position it must first be transformed to an input velocity, by for example scaling or differentiating.

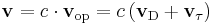

Thus the control signal  would be computed from the operator's input velocity

would be computed from the operator's input velocity  as:

as:

If  there exists a one-to-one mapping between the operator and the slave robot.

there exists a one-to-one mapping between the operator and the slave robot.

If the constant  is replaced by a diagonal matrix

is replaced by a diagonal matrix  it is possible to adjust the compliance independently for different dimensions of

it is possible to adjust the compliance independently for different dimensions of  . For example, setting the first three elements on the diagonal of

. For example, setting the first three elements on the diagonal of  to

to  and all other elements to zero would result in a system that only permits translational motion and not rotation. This would be an example of a hard virtual fixture that constrains the motion from

and all other elements to zero would result in a system that only permits translational motion and not rotation. This would be an example of a hard virtual fixture that constrains the motion from  to

to  . If the rest of the elements on the diagonal were set to a small value, instead of zero, the fixture would be soft, allowing some motion in the rotational directions.

. If the rest of the elements on the diagonal were set to a small value, instead of zero, the fixture would be soft, allowing some motion in the rotational directions.

To express more general constraints assume a time-varying matrix ![\mathbf{D}(t) \in \mathbb{R}^{6 \times n},~ n \in [1..6]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7f5a1d3401f69adcac1d317850735381.png) which represents the preferred direction at time

which represents the preferred direction at time  . Thus if

. Thus if  the preferred direction is along a curve in

the preferred direction is along a curve in  . Likewise,

. Likewise,  would give preferred directions that span a surface. From

would give preferred directions that span a surface. From  two projection operators can be defined (Marayong et al., 2003), the span and kernel of the column space:

two projection operators can be defined (Marayong et al., 2003), the span and kernel of the column space:

If  does not have full column rank the span can not be computed, consequently it is better to compute the span by using the pseudo-inverse (Marayong et al., 2003), thus in practice the span is computed as:

does not have full column rank the span can not be computed, consequently it is better to compute the span by using the pseudo-inverse (Marayong et al., 2003), thus in practice the span is computed as:

where  denotes the pseudo-inverse of

denotes the pseudo-inverse of  .

.

If the input velocity is split into two components as:

it is possible to rewrite the control law as:

Next introduce a new compliance that effects only the non-preferred component of the velocity input and write the final control law as:

References

- L. B. Rosenberg. Virtual fixtures: Perceptual tools for telerobotic manipulation, In Proc. of the IEEE Annual Int. Symposium on Virtual Reality, pp. 76–82, 1993.

- P. Marayong, M. Li, A. M. Okamura, and G. D. Hager. Spatial Motion Constraints: Theory and Demonstrations for Robot Guidance Using Virtual Fixtures, In Proc. of the IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation, pp. 1270–1275, 2003.

![\begin{align}

\textrm{Span}(\mathbf{D}) & \equiv \left[ \mathbf{D} \right] =

\mathbf{D}(\mathbf{D}^T\mathbf{D})^{-1}\mathbf{D}^T \\

\textrm{Kernel}(\mathbf{D}) & \equiv \langle \mathbf{D} \rangle = \mathbf{I} - \left[ \mathbf{D} \right]

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f56db3bf6a64d94a326076afa877bf45.png)

![\textrm{Span}(\mathbf{D}) \equiv \left[ \mathbf{D} \right] = \mathbf{D}(\mathbf{D}^T\mathbf{D})^{\dagger}\mathbf{D}^T](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/49e6f57d89941f8bd438883f3fadb61d.png)

![\mathbf{v}_\textrm{D} \equiv \left[ \mathbf{D} \right]

\mathbf{v}_\textrm{op} \textrm{~and~} \mathbf{v}_\tau \equiv

\mathbf{v}_\textrm{op} - \mathbf{v}_\textrm{D} = \langle \mathbf{D} \rangle

\mathbf{v}_\textrm{op}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e269bff9642f4210f5a95cd85e765aa7.png)

![\mathbf{v} = c \left( \mathbf{v}_\textrm{D} %2B

c_\tau \cdot \mathbf{v}_\tau \right) =

c \left( \left[ \mathbf{D} \right] %2B c_\tau \langle \mathbf{D} \rangle \right)

\mathbf{v}_\textrm{op}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/883494465eb44ec971f685413e22c706.png)